Be yourself; Everyone else is already taken.

— Oscar Wilde.

This is the first post on my new blog. I’m just getting this new blog going, so stay tuned for more. Subscribe below to get notified when I post new updates.

Be yourself; Everyone else is already taken.

— Oscar Wilde.

This is the first post on my new blog. I’m just getting this new blog going, so stay tuned for more. Subscribe below to get notified when I post new updates.

Summary

When looking at traditional conventions in Horror and Gothic films, the family has been the central plot line to many of these genre films. this is what Tony Williams suggested, as horror films often ‘present the monster as originating within the family’ (Williams, 1996). Famous films such as The Shining (1980) predominately feature a family, as well as The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974) and The Hills Have Eyes (1977). James Wan’s The Conjuring (2013) however, takes more of a maternal plot line, meaning the maternal figure either attempts or does kill children, allowing us to explore feminist ideas within the film.

In this film, we look at the maternal figures either being a threat to the peace. Sarah Arnold suggests that ‘maternal horror cinema’ films that sorely focus on maternal figures and perpetuate the ‘unstable ideology of idealised motherhood’, or the too invested mothering, seen in two archetypes: The Good mother and The Bad Mother (Arnold, 2013, p.4). When we think of the traditional motherhood conventions, this film along with others: The Others (2001) and Mama (2013), challenge these conventions and are now named ‘new momism… a cultural trend which surfaced in the 1990s and purports to celebrate motherhood by making mothers subservient to their children and no longer their husbands’ (Karyln, 2011, p.3).

What needs to be understood is how and what makes the maternal figure in The Conjuring scary. It has been suggested that audiences seek horror films ‘to feel horror…fear, the reaction one has at seeing something ghastly, loathsome, repellent or revolution, a reaction that dictionaries call “repugnance”‘ (Ochoa, 2011, p.5). So, how do mothers create fear and repugnance?

What needs to be understood is how and what makes the maternal figure in The Conjuring scary. It has been suggested that audiences seek horror films ‘to feel horror…fear, the reaction one has at seeing something ghastly, loathsome, repellent or revolution, a reaction that dictionaries call “repugnance”‘ (Ochoa, 2011, p.5). So, how do mothers create fear and repugnance?

Theorists that have researched the abject, grotesque of horror films, especially within themes such as: gender, femininity and motherhood; Betterton (1996), Creed (1983), Kristen (1982) and Russo (1995). The way the abject and grotesque nature of motherhood figures have become present from the character’s reaction of normal motherhood, almost like rebelling. These mother figures are mentally and physically grotesque, and by creating these idea and imbedding them into the films, directors warp the typical ideas and attitudes of women and mothers.

When beginning to understand the feminist approaches to horror films, Freeland’s ‘feminist framework’ helps explain how The Conjuring creates horror through the representations of ‘gender, sexual and power relation’ however, also interpreting ‘certain naturalised messages about gender…that the film takes for granted and expects its audience to agree and accept’ (Freeland, 1992, p.752).

The Conjuring is based around the idea of Good Mother versus Bad Mother, which has been ‘constructed within dominant patriarchal culture’ (Arnold, 2013, p.4). A Good Mother is to ‘self-sacrifice, selflessness and nurturance’ (Arnold, 2013, p.37), she thrives on doing what is best for her child, not depending on her own health and wellbeing. Whereas, a Bad Mother, is ‘a multifaceted and contradictory construction’, someone who completely rejects motherhood and what it stands for. In an analysis of The Babadook (2014), ‘while motherhood is now framed as a choice, the caveat is that the woman must choose to give herself over to the child entirely if the child is to succeed’ (Quigley, 2016, p.65). The Conjuring, has the same ideology, as we begin to understand the conflicting presence of Good versus Bad Mother and to identify if this film disassembles the myth of idealised motherhood.

An important way in identifying the abject and grotesque is through the use of dialogue, ‘exaggeration, hyperbolism and excessiveness are generally considered fundamental attributes of the grotesque style’ (Bakhtin, 1984, p.303). The grotesque body ‘ceases to be itself’ meaning it line between the body and the world vanishes, allowing ‘one to be with the other with the surrounding objects’ (Bakhtin, 1984). In a grotesque body, physical features such as body party become disgusting and the body is unable to perform everyday acts such as: eating, drinking or pregnancy. The grotesque body is never complete, it is constantly deteriorating, ‘it continually builds and creates another body’ (Bakhtin, 1984).

To understand the connection between gender and the grotesque, Mary Russo suggests that its the grotesque which sways away from and rejects normal ideals of behaviour and the body (Russo, 1995, p.10). Therefore, the ‘female’ body becomes grotesque as it becomes to slowly become more disgusting as Bakhtin argued. It is very similar to how horror films which include non-human monsters. Not only have the mother figures in The Conjuring become grotesque, but they also deform the normal boundaries mothers are supposed to do.

In terms of the abject, is is suggested that the abject is the human reaction to the threat of a breakdown in meaning or a loss of distinction between subject and object (Kristeva, 1982, p.5). She continues by arguing that ‘an archaic relationship to the object interprets, as it were, the relationship to the mother…her being coded as ‘abject’ (Kristeva, 1982, p.64).

It is argued that the borders and boundaries between mother and child are ‘central to the construction of the monstrous’ in horror films (Creed, 1986, p.44). Creed also examines how women are represented in horror films as being monstrous in terms of their relationship with their children (Creed, 1986, p.54). This is known as the ‘archaic mother’ (Creed, 1986). In horror films, the archaic mother is seen a grotesque and as someone who has a desire to maintain a relationship with her child.

A classic film which has representations of a grotesque mother is Carrie (1976) by Stephen King. Carrie’s single mother is seen to be emotionally and physically violent abusive to her daughter. Carrie is unable to escape her mothers grasp, and in the end, the film concludes with her filling her classmates, mother and herself.

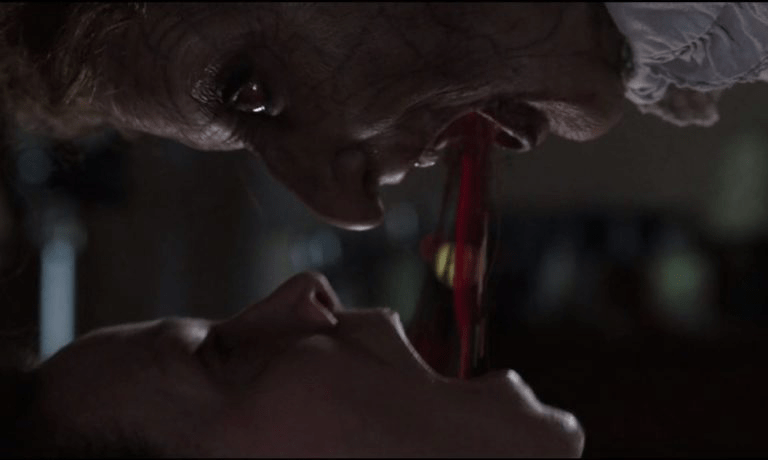

When analysing The Conjuring which is set in 1971, the film is entirely based on the mother, Carolyn, being possessed and attempts to kill her children. Therefore, it is clear that she plays the Bad Mother, as she becomes grotesque in her manner and appearance.

This maternal figure, slowly become more and more physically grotesque, as Bakhtin (1984) suggested, ‘the limits between the body and the world are erased, leading to the fusion of the one with the other and with surrounding objects’. The primary mother figure in The Conjuring is of course Carolyn, at the beginning of the film it is shown how much she cares for her children and how she continues to put her children and her husbands needs before her own, she is not the antagonist. Throughout the film, she become more and more possessed by a maternal antagonist, the demon Bathsheba.

Not all physical grotesqueness happens in the same way. for example, in The Others (2001), Grace becomes mad as she finds it too stressful to look after her terminally ill children. whereas, in The Conjuring, Carolyn is possessed by a demon as she is ‘the most psychologically vulnerable’ of the family, therefore she inherits the typical conventions of a demon.

In The Conjuring, none of the children came away unharmed, the children will never trust their mother again. Maternal horror films continue to twist the social conventions of normal mother-child relationship in their homes. In society, we have been made to believe and trust in the idea that ‘women’ are more nurturing, caring and empathetic. they have been socially constructed this way. Therefore, when mothers are seen as completely opposite in horror films, the audience are instantly scared as it is completely against the norm.

Bibliography:

Arnold, S. (2013). Maternal Horror Film: Melodrama and Motherhood. New York: Palgrave Macmillian.

The Babadook, (2014). Jennifer Kent. USA: IFC Films.

Bakhtin, M. (1984). Rabelais and his World. Translated by Helene Iswolsky. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Betterton, R. (1996). An Intimate Distance: Women, Artists and the Body. New York: Columbia University Press.

Carrie. (1976). Brian De Palma. USA: United Artists.

The Conjuring. (2013). James Wan. USA: New Line Cinema.

Creed, B. (1986). ‘Horror and the Monstrous-Feminine: An Imaginary Abjection’. Screen. 27(1). pp.44-71.

Freeland, C. (1992). ‘Feminist Frameworks for Horror Films’, in Leo Braudy and Marshall Cohen (eds.), Film Theory and Criticism, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 742-763.

The Hills Have Eyes, (1977). Wes Craven. USA: Vanguard.

Karlyn, K. (2011), Unruly Girls, Unrepentant Mothers: Redefining Feminism on Screen, Austin: University of Texas Press

Kristeva, J. (1982), Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection, New York: Columbia University Press.

Mama, (2013). Andy Muschietti. USA: Universal Pictures.

Ochoa, G.(2011), Deformed and Destructive Beings: The Purpose of Horror Films, Jefferson: McFarland.

The Others. (2001) Alejandro Amenábar. USA: Dimension Films.

Quigley, P. (2016), ‘When Good Mothers Go Bad: Genre and Gender in The Babadook’, Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies, Vol. 15, pp. 57-75.

Russo, M. (1995), The Female Grotesque: Risk, Excess, and Modernity, New York: Taylor and Francis.

The Shining, (1980). Stanley Kubrick. USA: Warner Bros.

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, (1974). Tobe Hooper. USA: Bryanston Distributing.

Williams, T. (1996), Hearths of Darkness: The Family in the American Horror Film, Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press.

Word Count: 1668.

This is an example post, originally published as part of Blogging University. Enroll in one of our ten programs, and start your blog right.

You’re going to publish a post today. Don’t worry about how your blog looks. Don’t worry if you haven’t given it a name yet, or you’re feeling overwhelmed. Just click the “New Post” button, and tell us why you’re here.

Why do this?

The post can be short or long, a personal intro to your life or a bloggy mission statement, a manifesto for the future or a simple outline of your the types of things you hope to publish.

To help you get started, here are a few questions:

You’re not locked into any of this; one of the wonderful things about blogs is how they constantly evolve as we learn, grow, and interact with one another — but it’s good to know where and why you started, and articulating your goals may just give you a few other post ideas.

Can’t think how to get started? Just write the first thing that pops into your head. Anne Lamott, author of a book on writing we love, says that you need to give yourself permission to write a “crappy first draft”. Anne makes a great point — just start writing, and worry about editing it later.

When you’re ready to publish, give your post three to five tags that describe your blog’s focus — writing, photography, fiction, parenting, food, cars, movies, sports, whatever. These tags will help others who care about your topics find you in the Reader. Make sure one of the tags is “zerotohero,” so other new bloggers can find you, too.